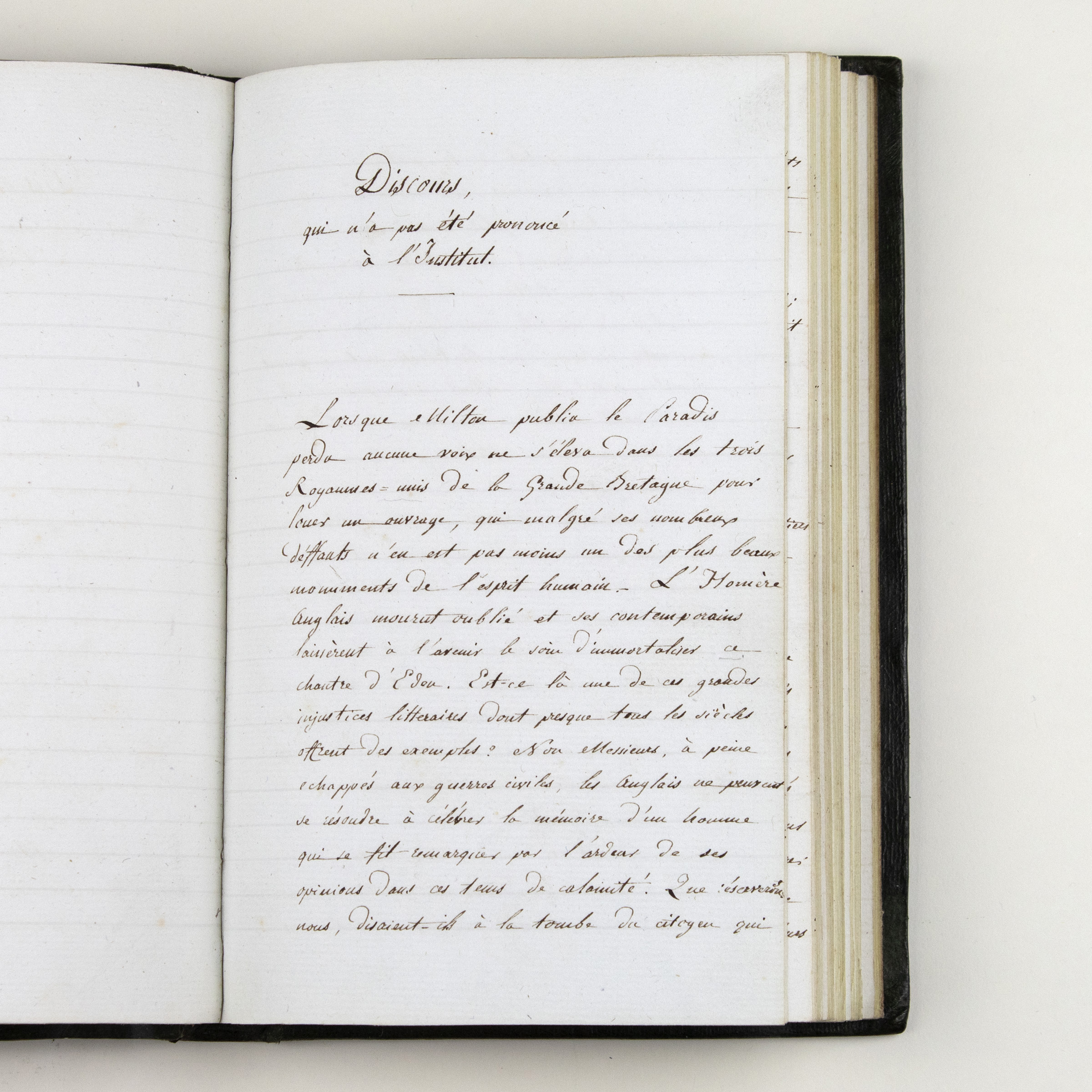

Discours qui n’a pas été prononcé à l’Institut. [Followed by] [STAËL-HOLSTEIN (Germaine de)]. Fragments inédits de Madame de Staël.

[1811-1813].

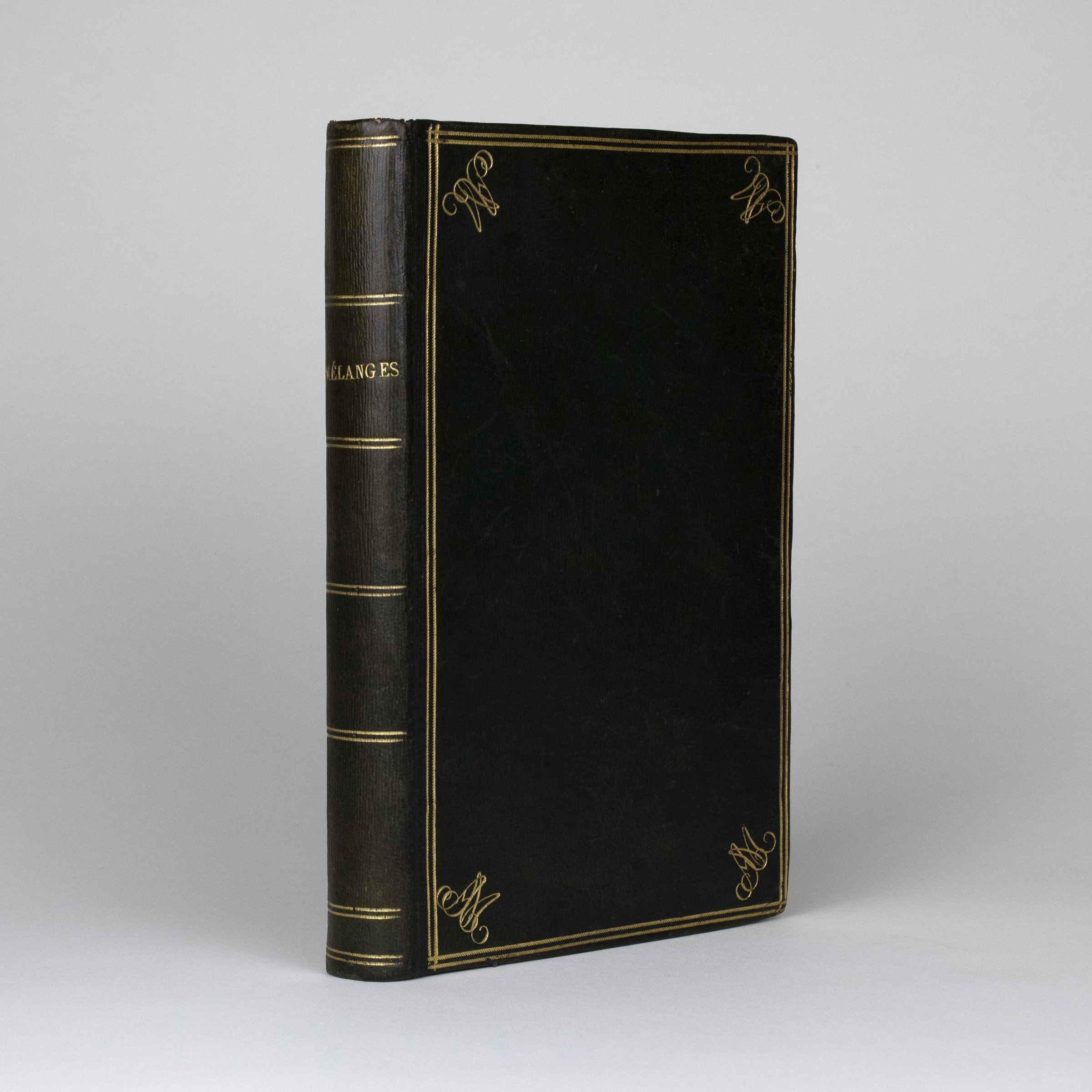

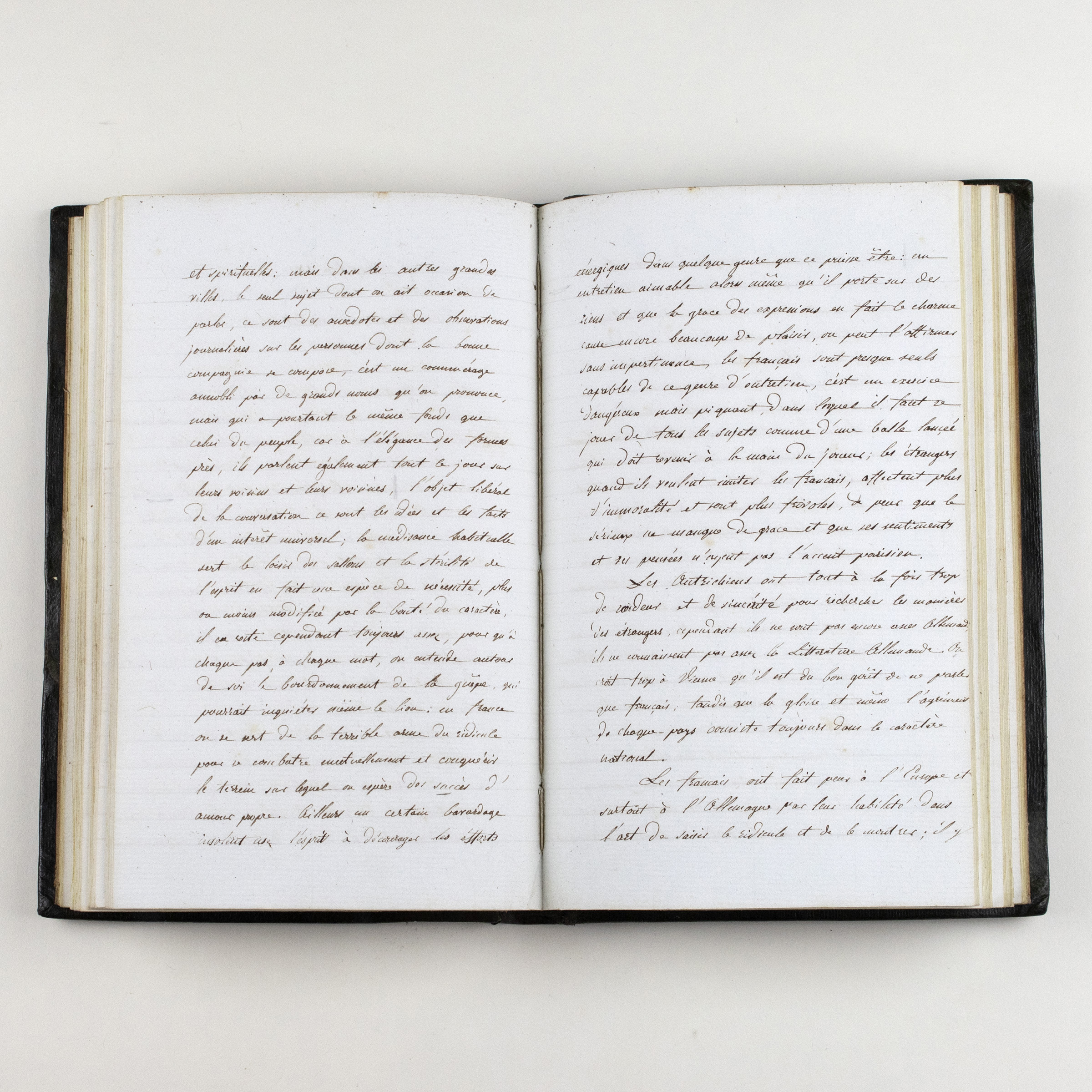

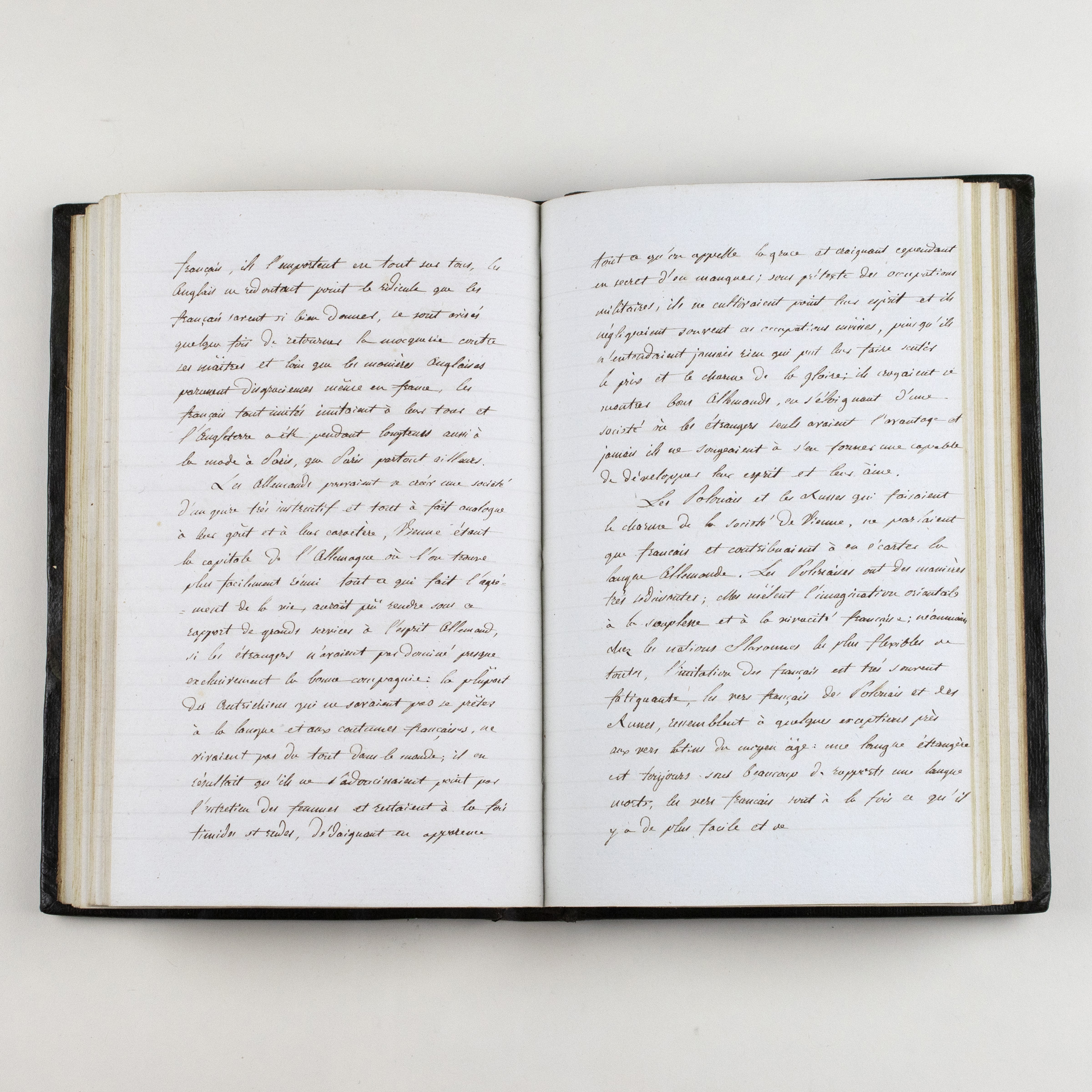

In-8 (205 x 140 mm), 20 pp. for the Discours, 23 pp. for the Fragments, with some thirty blank leaves before and after the copies, green morocco, double gilt fillet, gilt AM numeral at corners, smooth spine titled Mélanges, jonquille edges (Bound in the period with the head-and-tail label of Michel Janet Papetier Rue St. Honoré N°218, Paris).

A PERIOD MANUSCRIPT COPY OF TWO WORKS THAT WERE CENSORED BY BONAPARTE'S POLICE AND CIRCULATED UNDER THE CLOAK: CHATEAUBRIAND'S RECEPTION SPEECH AT THE INSTITUTE AND FRAGMENTS OF MADAME DE STAËL'S DE L'ALLEMAGNE.

THESE TWO FORBIDDEN TEXTS WERE CIRCULATED AT THE TIME THANKS TO COPIES THAT ENABLED A FEW PRIVILEGED ENTHUSIASTS TO BECOME ACQUAINTED WITH THEM.

MANUSCRIPT COPIES OF CHATEAUBRIAND'S SPEECH ARE RARE TODAY, ALTHOUGH A NUMBER OF THEM ARE PRESERVED IN INSTITUTIONS.

MANUSCRIPT COPIES OF DE L'ALLEMAGNE, ALWAYS FRAGMENTARY IN VIEW OF THE MONUMENT, ARE EXTREMELY RARE.

THEY ARE EVEN MORE RARE AS THEY PREDATE THE FIRST EDITION IN COMMERCE (London, Murray, 1813), AS THE TITLE OF THIS COPY "FRAGMENTS INÉDITS" INDICATE.

WE HAVE FOUND NO TRACE OF SUCH A COPY IN ANY INSTITUTION.

THE REUNION OF THESE TWO CENSORED AND INACCESSIBLE WORKS, CALLIGRAPHED BY AN AMATEUR OF THE PERIOD, IS QUITE EXCEPTIONAL.

The speech that was not delivered at the Institut de France

"Monsieur de Chénier died on 10 January 1811. My friends had the fatal idea of urging me to replace him at the Institut" (Mémoires d'outre-tombe).

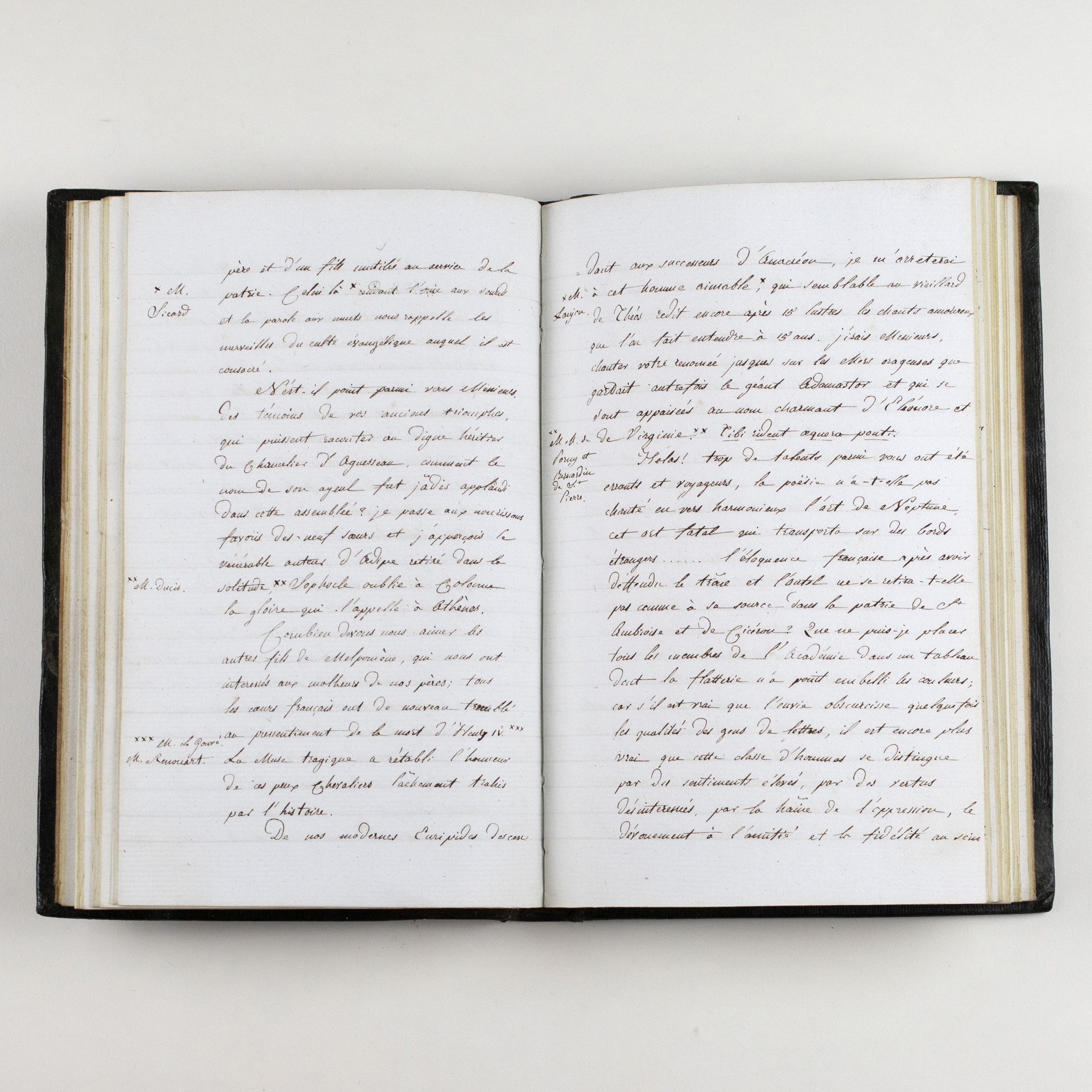

Chateaubriand was elected to the Institut on 20 February 1811 and, as tradition demanded, was required to give a speech on the day of his reception in which he was supposed to praise his predecessor. He could not bring himself to honour the memory of Marie-Joseph Chénier (1764-1811), revolutionary, regicide and, in his time, contemptor of the Génie du christianisme.

The speech was given to Napoleon Bonaparte who, according to Chateaubriand, "crossed out here and there" the manuscript, "marked ab irato with brackets and pencil marks". "The lion's nail was sunk in everywhere, and I had a sort of irritating pleasure in believing I could feel it in my side." (MOT)

Chateaubriand refused to change his speech and was not admitted to the Institut. He did not take his seat until the Restoration.

"This speech is one of the best proofs of the independence of my opinions and the constancy of my principles" (MOT).

The affair caused quite a stir and numerous copies were circulated, all of which were disowned by the author, who only published the text in the Mémoires d'outre-tombe after 1845.

Although disowned, the period copies are very close to the text of the Mémoires d'outre-tombe, as Chateaubriand inserted the text from a copy sent by one of his colleagues at the Institut.

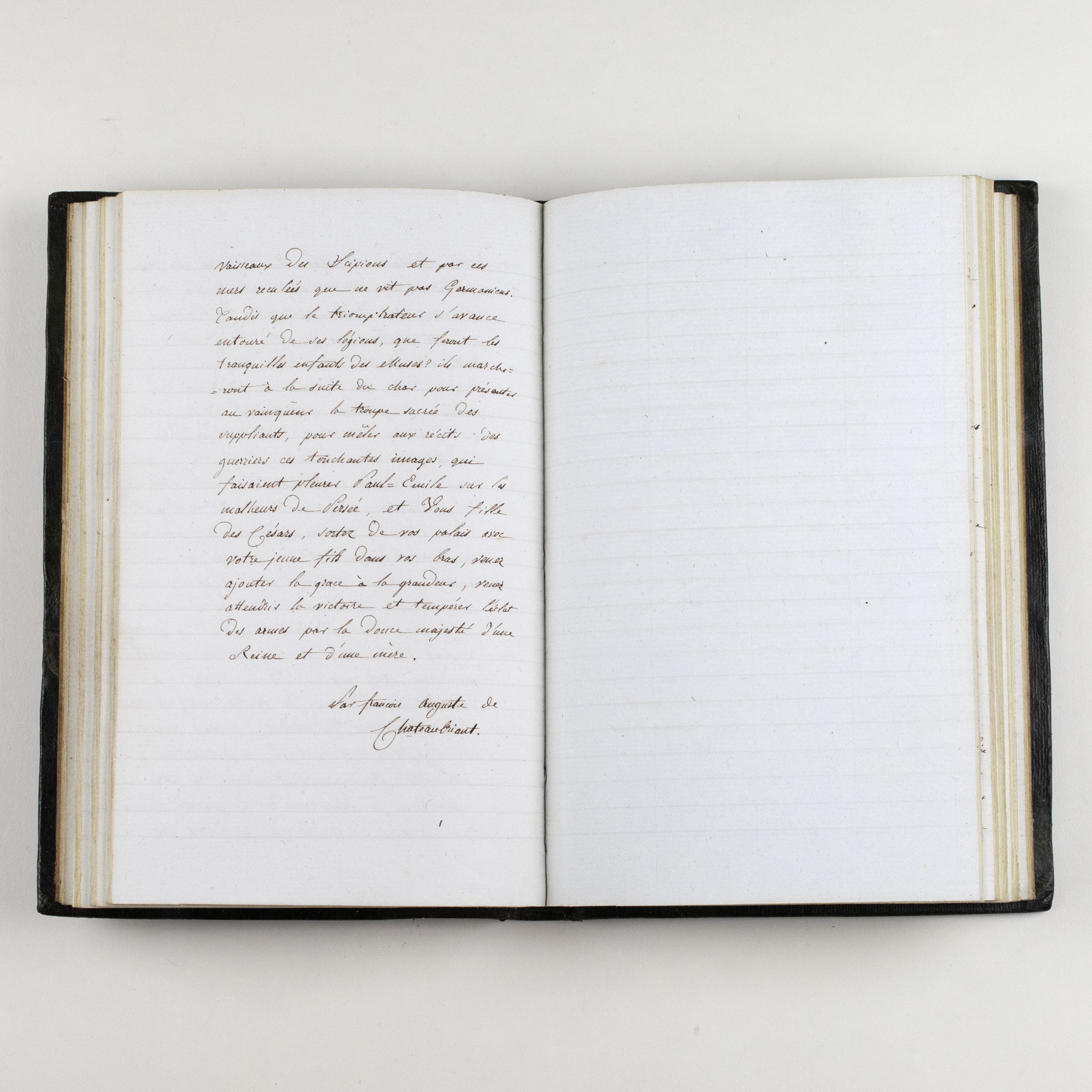

Entitled Discours qui n'a pas été prononcé à l'Institut, the copy we are presenting is signed François-Auguste de Chateaubriant (sic), a spelling often used at the time. It contains in the margin the names in plain text of the people to whom Chateaubriand refers.

The text is very close to that of the Mémoires d'outre-tombe and contains variations that are specific to the condition in which it was copied, such as the replacement of one word by another, the addition or deletion of words, the use of the plural instead of the singular and vice versa, changes of tense, etc.

The phrase "Un Français fut toujours libre aux pieds du trône" ("A Frenchman was always free at the foot of the throne") appears in period copies but was not included in the Mémoires d'outre-tombe (1).

Madame de Staël's unpublished fragments: three chapters of De l'Allemagne

"This wide-ranging work, which is at once political, philosophical, literary and critical, is remarkably harmonious and free-thinking" [...]. "De l'Allemagne is one of the fundamental books of the 19th century, and the one through which the French were most widely introduced to German literature and philosophy."

In french in the text, n°222.

De l'Allemagne is one of Madame de Staël's major works, part travelogue, part reflection on philosophy, the fine arts, literature and religion. It is also a powerful political work, challenging French domination of Europe in both the arts and politics.

The work could not escape imperial censorship, as Napoleon considered it hostile to France and detrimental to its influence abroad. The entire edition was therefore seized and destroyed in 1810, and only a few copies of the first edition remained. Forced to leave France, Madame de Staël retired to Coppet and persisted in publishing her work.

"During her exile in 1812-1814, Mme de Staël read a number of passages from her manuscript to selected audiences, first in Coppet, then in the various European countries she travelled through". Axel Blaeschke (2)

Handwritten copies circulated: "In France, during the last months of the imperial regime, extracts from Mme de Staël's book circulated under the cloak and clandestine readings were given in small groups". Countess Jean de Pange (3)

De l'Allemagne was finally published at the end of October 1813 in London, then in Paris in 1814.

The copies mentioned by the Comtesse Jean de Pange were in circulation before April 1814 and must have been based on the 1813 edition, since the Paris edition did not appear until after Madame de Staël's return to Paris in May 1814.

The title of our copy, "Fragments inédits", seems to indicate that it is a copy prior to the London edition of 1813.

As with Chateaubriand's speech, the text is close to the printed version, but contains many variations in words, conjugation and punctuation (see pdf De l'Allemagne - comparaison des textes de 1810, 1813 et copie manuscrite, sent by email on the 26th of october.

This copy contains chapters III Les femmes, IV De l'influence de l'esprit de chevalerie sur l'amour et l'honneur, and more than half of chapter IX Des étrangers qui veulent imiter l'esprit français. These chapters are contained in the first part of De l'Allemagne et des mœurs des allemands.

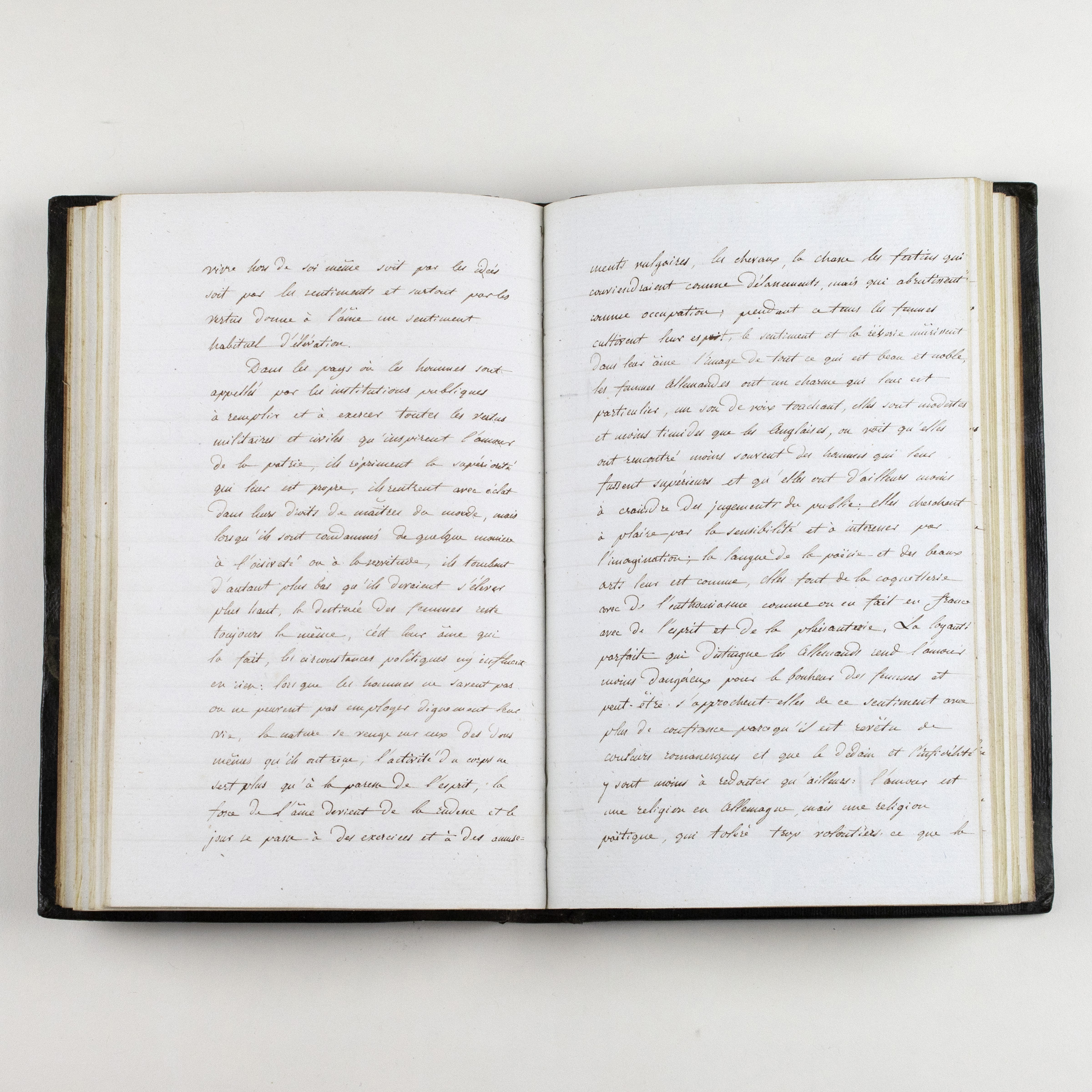

The chapter Des Femmes paints a portrait of German women by comparing them to French women and describing their relationship to society, the arts and men.

It has its origins in the "impressions that [Madame de Staël] received from meeting women during her visits to Frankfurt, then Weimar, Berlin and Vienna. See [...] her letter of 10 December 1803 to Necker, in which she is highly critical of "German men" in favour of women (Correspondance générale V/1, p.134-135 [...]" (4).

The chapter opens as follows: "Nature and society give women a great habit of suffering, and it cannot be denied, it seems to me, that nowadays they are generally better than men."

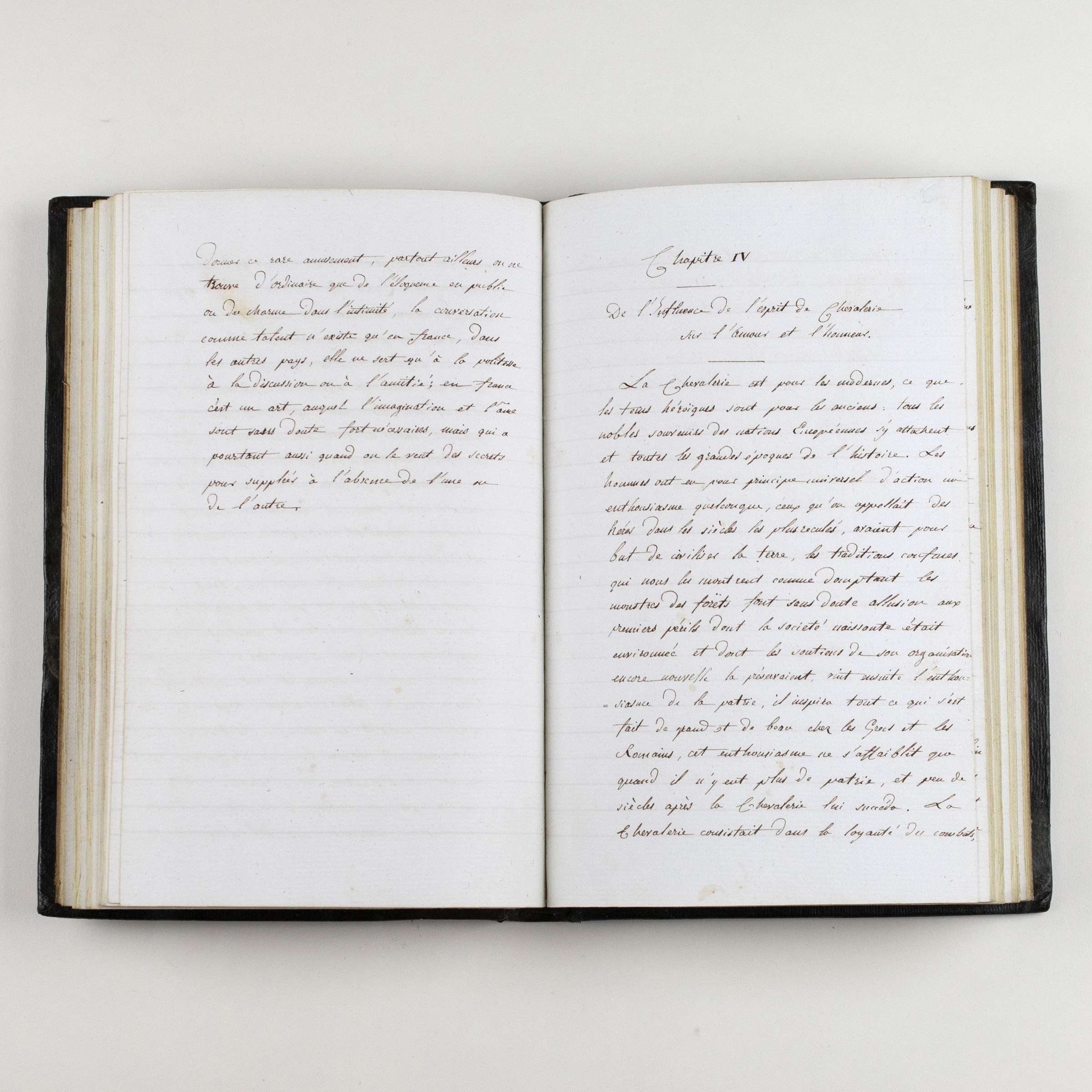

In chapter IV, De l'influence de l'esprit de chevalerie sur l'amour et l'honneur (The influence of the spirit of chivalry on love and honour), Madame de Staël laments the disappearance of the spirit of chivalry that once animated the French, in contrast to Germany which, "with the exception of a few courts eager to imitate France, was not affected by the fatuity, immorality and incredulity which, since the Regency, had altered the natural character of the French". Women are once again a central subject in this chapter, with Madame de Staël depicting, among other things, the lack of esteem from which women can suffer in France, due to the loss of the spirit of chivalry.

This chapter resonates with the literary productions of the Coppet Group. "Chivalry was a key concept within the Coppet Group. Sismondi treated it as a historian (History of the Italian Republics), August Wilhelm Schlegel as a literary critic in his Vorlesungen über schöne Literatur und Kunst, under the heading of "Mythologie des Mittelalters" (Course on Literature and the Fine Arts: Mythology of the Middle Ages)." (5)

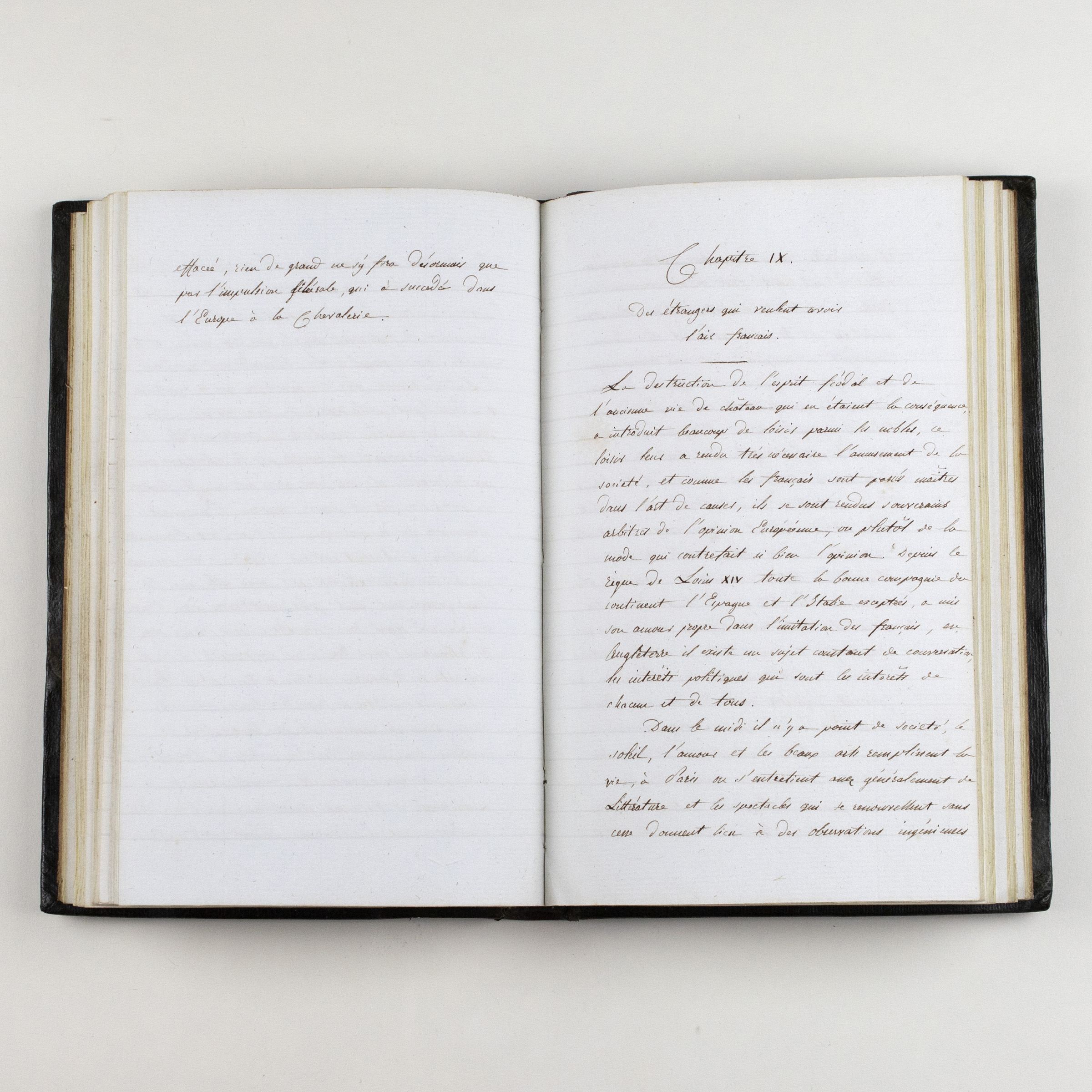

Finally, in the chapter Des étrangers qui veulent imiter l'esprit français, Madame de Staël criticises the fact that most of France's neighbours seek to imitate its manners, including backbiting and gossip, without cultivating their national differences and particularities: "there is too much belief in Vienna that it is in good taste to speak only French; whereas the glory and even the pleasure of each country always consist in its national character and spirit".

Although this chapter was not copied in full in our copy, it contains one of the passages that posed a particular problem for Napoleon and his censors: "The ascendancy of French manners has perhaps prepared foreigners to believe them invincible. There is only one way of resisting this ascendancy: it is through very determined national habits and customs."

The fact that these copies were calligraphed by an amateur of the time in a pretty morocco notebook is quite exceptional.

As we were unable to consult copies of De l'Allemagne, the copies of Chateaubriand's speech that we were able to examine were either in sheets, stapled, or bound afterwards for bibliophile purposes.

The copy we have here bears witness to the copyist's admiration for these two important figures of French literature, and particularly for their freedom of thought. Logically, it was copied on two separate copies of each of the texts. According to our observations and comparisons, it was not copied from a printed version of one of the texts.

The copyist must have been close to the intellectual and literary circles of the time, for if it was not easy to obtain a copy of Chateaubriand's speech, it must have been extremely difficult to obtain passages from De l'Allemagne, especially before 1813, when the work was still unpublished.

(1) Pierre Grossetête. Le Discours de réception de Chateaubriand à l'Académie française et ses variantes. in Bulletin n°36 de la Société Chateaubriand (1993) pp. 6-15

(2, 4, 5) Staël. Complete works. Série I. Tome III. De l'Allemagne. Text established, presented and annotated by Axel Blaeschke. Paris, Champion, 2017. p. 62, p.111, p. 115

(3) Staël. De l'Allemagne. New edition [...] by Comtesse Jean de Pange with the assistance of Simone Ballayé. Paris, Hachette, 1958. p. xxxiv

8 000€

En stock

Nous contacter